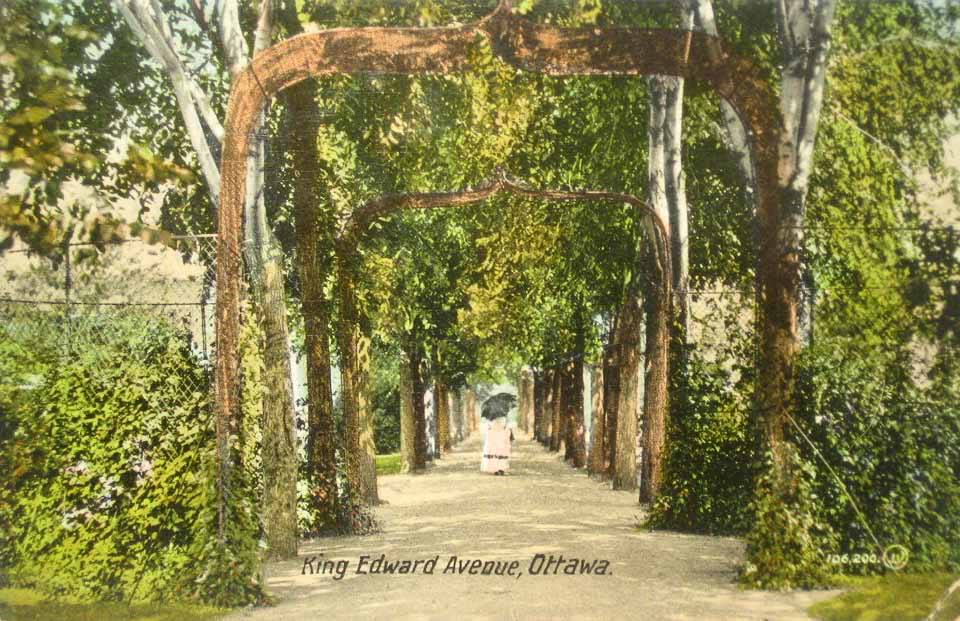

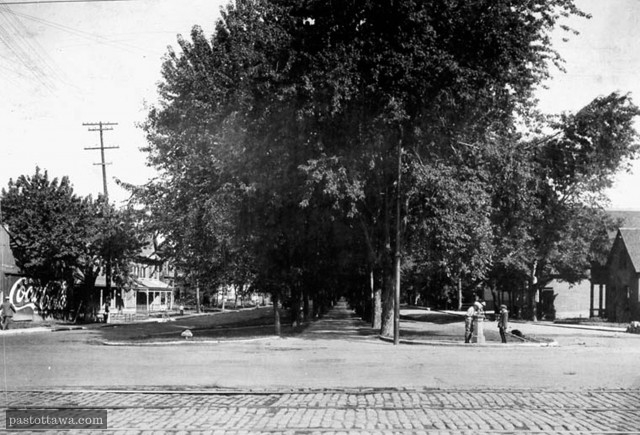

| Article written by Graham Saul. Reprinted from The Lowertown Echo, Vol 6, Issue 5: Dec 2015. Lowertown residents know that King Edward Avenue is a perfect example of car culture gone wild. The city sacrificed pedestrian and cycling safety, and chopped down a beautiful tree-lined boulevard to make King Edward into a highway in the downtown core. But King Edward Avenue was not an accident, it was the logical extension of bad urban planning. Recent events at city hall hold out the possibility that we can avoid this kind of mistake in the future, and maybe even move King Edward Avenue in the right direction. |

Last month, Ottawa’s City Council took an important step to correct this mistake and put us on the road to safer and healthier neighbourhoods.

Fifty years ago, the concept of “level of service” must have seemed like a logical way of evaluating our transportation system’s performance, so it is not surprising that the idea was later enshrined in Canadian guidelines and became a core principle in how we build our roads. If you are a traffic engineer, you probably like the idea of having a simple, specific set of criteria to assess a given road, and level of service provides you with a way to do just that.

Unfortunately, if you are a resident in Lowertown or any other urban area and you like the idea of liveable neighbourhoods with a variety of safe transportation options, it was a recipe for disaster and left us with King Edward Avenue, a highway dividing our community. Not only do residents fear crossing it, many pedestrians have been killed and injured doing so. The intersection at King Edward and Rideau has a tragic history; and at King Edward and St. Andrew, despite the traffic cameras, cars routinely whizz through the red light at well-above-limit speed.

If all an engineer has is a hammer, then everything starts to look like a nail, and if all they are asked to measure is cars, then every street starts to look like a highway. The answer to every problem becomes “we need more, wider and faster roads.”

A commuter, stuck in traffic, might like the idea of more, bigger and faster roads, but what if you are a parent whose child needs to walk to school? What if you rely on a wheelchair to get around town or you are getting old and you just want to be able to walk safely to the shops? What if you are a single parent that cannot afford a car and relies on public transit to get to and from your job, or a cyclist that wants to ride to work without feeling like you are taking your life into your own hands?

Perhaps most importantly, what if you see the street you live on as a place, a destination, part of a neighbourhood, and not just a thoroughfare for cars?

If you are any of these people, then you are not adequately represented when the traffic engineer sits down to assess a given road. You are not included in the level of service formula.

So let’s put aside the fact that building more and bigger roads does not actually solve congestion - if it did, Los Angeles would be a driver’s paradise instead of a traffic jam sitcom cliché. Let’s also not get bogged down in the overwhelming evidence that our dependence on cars has created health and environmental problems that need to be addressed urgently.

Instead, let’s just agree that we need a way of designing streets that takes everyone’s safety and comfort into consideration, regardless of their age, ability or mode of transportation.

That is what the City of Ottawa is now trying to do. It is called a “Complete Streets” approach, and the concept has been adopted by over 700 municipalities across North America, including Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver and Toronto. The City of Ottawa agreed to adopt a complete streets policy in its 2013 Transportation Master Plan, and they have now adopted a detailed implementation framework to put the policy into practice.

Instead of having only one level of service (for cars), we will now have a level of service criteria for all modes of transportation: cars, pedestrians, cyclists, public transit and trucks. This will not be a cookie-cutter approach - different kinds of roads serve different purposes and will continue to be designed in different ways. However, if you walk, cycle or take public transit, you will no longer be left out of the traffic engineer’s formula.

This sounds like a small step, but it is actually a small revolution in the way we design our roads.

Graham Saul is a Lowertown resident and the Executive Director of Ecology Ottawa, a grassroots environmental organization working to make Ottawa the green capital of Canada.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed